The Sanskrit Reading Room 2019/2020 was inaugurated on 2.10.2019 with a special performance and lecture by Ananth Rao of ANU Canberra. He was accompanied by Aparna Rao on the keyboard. This is a summary by ROHINI BAKSHI

audio

video (part 1, part 2, part 3)

Editing, recordings and images by Lidia Wojtczak

Dr. Rao’s musical recitation and exposition of selected verses from the Rāmāyaṇa began with an invocation. He chanted six verses, the first three of which were addressed to Viṣṇu, Gaṇeśa and Madhvācarya. The next three were addressed to Vālmīki, Vyāsa and Śuka – renowned for their contribution to ancient Indian literature. He explained that it was customary to begin with such an invocation irrespective of whether the setting was devotional or secular.

śuklāmbaradharaṃ viṣṇuṃ śaśivarṇaṃ caturbhujam

prasannavadanaṃ dhyāyet sarvavighnopaśāntayeagajānana padmārkaṃ gajānanaṃ aharniśam

anekadaṃtaṃ bhaktānāṃ ekadantaṃ upāsmaheLakṣmīnārāyaṇaṃ vande tadbhaktapravaro hi yaḥ

śrimadānandatīrthākhyo gurustaṃ ca namāmyahamkūjantaṃ rāmarāmeti madhuraṃ madhurākṣaraṃ

āruhya kavitāśākhaṃ vande vālmīki-kolilamnamo’stute vyāsa-viśāla-buddhe phullāravindāyata-patra-netra

yena tvavā bhārata-taila-pūrnaḥ prajvālito jñānamayo pradīpaḥnigama-kalpa-taror galitaṃ phalaṃ

śuka-mukhād amṛta-drava-saṁyutampibata bhāgavataṃ rasam ālayaṃ

muhur aho rasikā bhuvi bhāvukāḥ

Dr. Rao translated the verses pertaining to the literary giants of the Indian tradition. Firstly, Vālmīki who is considered the first poet (ādi kavi) and author of the Rāmāyaṇa. Secondly, Vyāsa who tradition considers the creator of the Mahābhārata and finally Śuka, through whose mouth the third ‘epic’ – the Bhāgavatam was rendered. Dr. Rao qualified the use of the word epic for this text, saying it was more a religious and devotional text as compared to the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata which are considered ‘itihāsa’ (roughly translated as history). The latter he said were in their original form more secular – with only limited elements of religiosity. Coming back to the Bhāgavatam, he suggested that it was ‘epic’ in its proportion, dimensions and themes.

More germane to the performance was the import of the śloka nigama-kalpa-taror galitaṃ phalaṃ, śuka-mukhād amṛta-drava-saṃyutam – because it set the tone of how one should approach a performance. Emerging from the mouth of Śuka (literally – a parrot), the Bhāgavatam was the liquified nectar (amṛta–drava) of the ripe fruit (galita-phalam) of the tree that is Veda (nigama-kalpa-taru). It was the receptacle of enjoyment (rasam ālayaṃ) which was drunk or enjoyed (pibata) incessantly (muhur) on earth (bhuvi) by connoisseurs (rasikāḥ) and those who have rich inner imagination (bhāvukāḥ). In short, even if a key theme of a text is austerity, interacting with it must be an aesthetic experience and the primary goal is the enjoyment of the text. It should be an uplifting experience, taking the audience to a higher dimension.

He touched briefly upon gargantuan scope and grandeur of the Mahābhārata. 100,000 verses and the text’s own claim that anything that is found in the Mahābhārata can be found elsewhere, but what you cannot find in the Mahābhārata will not be found anywhere else either. (yad ihāsti tad anyatra yan nehāsti na tat kutra cit). He quoted Peter Brook whose nine-hour French play based on the Mahābhārata caused a sensation when it was first staged in 1985. Brook, when asked in a radio interview which play of Shakespeare Mahābhārata came close to, responded by saying that all of Shakespeare’s works put together might approximate the epic, and that too partially. While this may be an unsubstantiated claim, Dr. Rao said it demonstrated the regard in which the epic was held not just at home, but around the globe.

After this he moved to the Rāmāyaṇa which was the topic of his performance for this session. Dr. Rao, although a mathematician by vocation, is an experienced and skilled performer of ancient Hindu texts. His renditions straddle two traditional oral performance styles – purāṇapravacana and harikathā. In purāṇapravacana, stories are told using actual textual material from the epics—usually from the Rāmāyaṇa, Mahābhārata, or one of the eighteen purāṇas. The presenter, called a paurāṇika, is typically a scholar of some standing. The textual material is recited in Sanskrit and then interpreted in a regional language. The harikathā style of storytelling, sometimes known as kathākālakṣepa, also draws its stories from the epic and purāṇa texts. However, rather than relying predominantly on Sanskrit texts, the performance relies more on musical rendering of songs in the regional languages, principally from the bhakti (devotional) literature which incorporates stories from the epics. 1

Dr. Rao then explained his invocatory tribute to Vālmīki, the legendary poet to whom the authorship of the Rāmāyaṇa is ascribed. Rāmāyaṇa being regarded as the first poetic work in the Indian tradition (ādi-kāvya), giving him the title ādi-kavi:

kūjantaṃ rāmarāmeti madhuraṃ madhurākṣaraṃ

āruhya kavitāśākhaṃ vande vālmīki kolilam“I salute Vālmīki [the] cuckoo cooing the sweet, sweet words ‘Rāma, Rāma’, perched on the branch [that is] poetry.”

Dr. Rao was less concerned with the historical veracity of the ‘ādi-ness’ of this poet and his work. However, he stressed that in fact the Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa had functioned as an ādi-kāvya inspiring a multitude of creative expressions – musical, literary, sculptural and performative. This was true not just of India, but of any culture where the Sanskrit cosmopolis spread. Given the depth and breadth of its influence, it is de facto an ādi-kāvya. Famous playwrights and authors not just of Sanskrit but even regional Indian languages have re-written parts or all of the Rāmāyaṇa – not as a challenge but as a tribute to Vālmīki. For instance, the Raghuvaṃśa of Kālidāsa. Even though Kālidāsa had his own perspective and deviated from Vālmīki now and again, he doffs his hat substantially to ‘greats’ of yore:

(atha vā) kṛtavāgdvāre vaṃśe ‘smin pūrvasūribhiḥ

maṇau vajrasamutkīrṇe sūtrasyevāsti me gatiḥ (Raghuvaṃśa 1.4)The door of speech (vāgdvāra) has already been created by learned poets of the past (pūrvasūribhiḥ) … my path (me gatiḥ) is like a thread (sūtrasyevāsti) going through a gem which has been perforated by a diamond-pin (maṇau vajrasamutkīrṇe).

Dr. Rao then expanded on the purpose of this session – to understand what the circumstances were surrounding the writing of this epic. What inspired the creation of this great book? This is explained in the first four sargas of the first book of the Rāmāyaṇa, called Bālakāṇḍa (the book of boyhood). He mentioned in passing that the epic has six plus one kāṇḍas (branches, books). Six major books and then a sequel, as he put it. There is some scholarly speculation regarding the authorship of the ‘sequel’ which is called Uttarakāṇḍa. However, the content of this book has so gripped the imagination of its audiences, said Dr. Rao, that irrespective of who wrote it, it is no longer possible to consider the content of the other six books without keeping this one in mind.

Dr. Rao sang the opening verses of the first sarga of Bālakāṇḍa. Incidentally, this sarga is known to the devout as Śataślokī Rāmāyaṇa (the Rāmāyaṇa of a hundred verses) and is chanted independently, as it is a summary of the whole epic. Dr. Rao’s performance followed the vulgate rather than the critical edition.

tapaḥsvādhyāyanirataṃ tapasvī vāgvidāṃ varam

nāradaṃ paripapraccha vālmīkir munipuṃgavam (Rām 1.1.1)

Vālmīki is the head of an āśrama and has a distinguished visitor. Dr. Rao stressed that an āśrama was not a hermitage, as it is often translated, but an academy. Rather than being a place one escapes to, it is a seat of learning. The detachment from the everyday concerns of society aims to encourage a deeper engagement with the those very concerns, as well as allowing students to remain undisturbed in study. So even though the āśrama is detached from society, Vālmīki, as the head of the academy, is very engaged with social issues and human destiny.

Now we turned to the distinguished visitor – the sage Nārada. Dr. Rao said with a twinkle in his eye, that Nārada was a very interesting and likeable character in Hindu mythology. He is a musician, a bard and a prankster who can travel freely anywhere in the universe. He features in most stories in the ancient texts – but never as a central character. He appears, sets something in motion and disappears. Dr. Rao in fact believes that the two great contributions of ancient India are the zero (śūnya) and Nārada! Both have no value in themselves, but without them, nothing happens.

The opening verse describes Nārada as constantly engaged in austerities and self-study (tapaḥsvādhyāyanirata). Despite being the repository of knowledge, he is forever improving himself. Sva-adhyāya is a very important part of the Indian scholarly tradition. When a student finishes his studies (and here Dr. Rao having added, ‘him or her’ was quick to acknowledge that it was rarely ‘her’ in the ancient texts) the teacher instructs, or rather admonishes the student:

svādhyāyapravacanābhyāṃ na pramaditavyam (Taittirīya Upaniṣad 1.11.1)

This academy-leaving injunction is among several laid out for the student. Dr. Rao likened it to advise given at a modern graduation ceremony. ‘Do not neglect self-study and transmission to others [of the knowledge you have obtained].’ Returning to Nārada, he is the best among eloquent speakers (vāgvidāṃ vara). Vālmīki, the tapasvin – asked (paripapraccha) Nārada a series of questions regarding the presence a man with superlative qualities.

ko nv asmin sāmprataṃ loke guṇavān kaś ca vīryavān

dharmajñaś ca kṛtajñaś ca satyavākyo dṛḍhavrataḥ (Rām 1.1.2)“Who, in our times is endowed with [virtuous] qualities, is valorous, the knower of dharma, who knows what needs to be done/knows what has been done, whose words are true and who is steadfast in his vows?”

cāritreṇa ca ko yuktaḥ sarvabhūteṣu ko hitaḥ

vidvān kaḥ kaḥ samarthaś ca kaś caikapriyadarśanaḥ (Rām 1.1.3)“Who has a good character, is compassionate to all beings; who is learned, capable and singularly pleasing to look at?”

In describing sarvabhūteṣu-hitaḥ, Dr. Rao explained this as a pervading idea in ancient India texts. Even Kṛṣṇa in the Bhagavad Gītā exhorts Arjuna to use the welfare of all beings as his guiding principle. But returning to the questions about the perfect being…

ātmavān ko jitakrodho dyutimān ko ‘nasūyakaḥ

kasya bibhyati devāś ca jātaroṣasya saṃyuge (Rām 1.1.4)

Dr. Rao interpreted ātmavān as someone possessing a certain sense of self which is free of arrogance and pride; jitakrodhaḥ – one who has conquered his anger; dyutimān – one who is shining, brilliant [like lightning] and anasūyakaḥ free of envy; of whom even the gods are afraid, when his rage is aroused in battle. Having outlined in four verses the perfect man he is in search of, he says to Nārada – “I am extremely curious to know/hear [and] you, O great ṛṣi are capable of knowing [of] such a person.” The important point here, said Dr. Rao was the use of ‘nara’ because one can always conceptualise of a super being, a supra-human with special qualities. But could such qualities be found in a mere ‘man’?:

etad icchāmy ahaṃ śrotuṃ paraṃ kautūhalaṃ hi me

maharṣe tvaṃ samartho ‘si jñātum evaṃvidhaṃ naram (Rām 1.1.5)

Nārada was very pleased to be asked, because after all he is vāgvidāṃ varaḥ, best among the eloquent and here is a chance to hold forth! While Vālmīki’s question lasted four verses, Nārada’s reply spans nearly ten verses. Dr. Rao continued singing, accompanied by his accomplished daughter Dr. Aparna Rao, who provided instrumental support. The two performers were as if of one breath. She anticipated his every musical need throughout the session.

śrutvā caitat trilokajño vālmīker nārado vacaḥ

śrūyatām iti cāmantrya prahṛṣṭo vākyam abravīt (Rām 1.1.6)bahavo durlabhāś caiva ye tvayā kīrtitā guṇāḥ

mune vakṣyāmy ahaṃ buddhvā tair yuktaḥ śrūyatāṃ naraḥ (Rām 1.1.7)“Having heard the words of Vālmīki, [Nārada] knower of the three worlds said: It is very difficult to find someone endowed with the characteristics you have specified – but, hear, O Muni, I know of one, and I will tell you about him.”

ikṣvākuvaṃśaprabhavo rāmo nāma janaiḥ śrutaḥ

niyatātmā mahāvīryo dyutimān dhṛtimān vaśī (Rām 1.1.8)“He was born in the Ikṣvāku lineage, (a solar dynasty which traces its origin to the sun) and he is known to the people as Rāma.”

rakṣitā svasya dharmasya sva janasya ca rakṣitā

vedavedāṅgatattvajño dhanurvede ca niṣṭhitaḥ (Rām 1.1.14)“He is a protector of his own code of conduct and protector of his own people; He understands the essence of the Veda and its ancillaries as well as being engaged in the science of archery.”

Dr. Rao explained that the term ‘veda’ was commonly added to any discipline that was profound or important, hence the art or the science of archery is called dhanurveda. The description of the perfect beings continued to unfold on musical notes. The perfect man, noble, learned, compassionate and strong. But there is more…

sa ca sarvaguṇopetaḥ kausalyānandavardhanaḥ (Rām 1.1.17a&b)

He is endowed with all [good] qualities and is the delight of Kausalyā, [his mother]. Having so described the perfect man, Nārada then set forth the story of entire Rāmāyaṇa in about one hundred verses, and Dr. Rao took us through the main points of the story swiftly. Apropos the organic unity of the epic and the place of the ‘sequel’ it is pertinent to mention here that this summary does not include the events of the Uttarakāṇḍa.

nāradasya tu tad vākyaṃ śrutvā vākyaviśāradaḥ

pūjayām āsa dharmātmā sahaśiṣyo mahāmuniḥ (Rām 1.2.1)yathāvat pūjitas tena devarṣir nāradas tadā

āpṛṣṭvaivābhyanujñātaḥ sa jagāma vihāyasam (Rām 1.2.2)

Having heard the words of Nārada, Vālmīki honoured him in befitting manner along with his disciples. Honoured thus, having taken and been given leave as per the rules of hospitality, Nārada went heavenwards – sa jagāma vihāyasam. Nārada appears from the sky, puts the idea of the perfect man, puts the idea that ‘good’ is possible in the world of men – into Vālmīki’s head and flies away. From above and back to heaven – Nārada represents the world of ideas, of imagination. Dr. Rao quoted from the Bhagavad Gītā to embellish this point.

ūrdhva-mūlam adhaḥ-śākham aśvatthaṃ prāhur avyayam

chandāṃsi yasya parṇāni yas taṃ veda sa veda-vit (BG 15.1)

This refers is the tree of imagination, the tree of inspiration. It has its roots above and the branches below – indicating that there is no limitation to ideas. The name of the tree ‘aśvattha’ Dr. Rao interpreted as ever changing. (a-śva-ttha) and imperishable, immortal (avyaya). Nārada represents this un-decaying yet ever-changing world of ideas. Vālmīki is inspired by him, so much so that he is left in a trance like state, contemplating the possibilities. He needs to root this tree in the physical, real world, the world of life – because it has no meaning otherwise. The tree of imagination has branches hanging down whereas the tree of reality is inverted, with its roots in the ground. The intervening space between the two is the world of creativity where literary and other magic happens. That is where Vālmīki, Einstein and Shakespeare reside.

After the departure of his esteemed guest, Vālmīki has the urge to go to the river – the symbol of reality and life par excellence.

sa muhūrtaṁ gate tasmin devalokaṁ munis tadā

jagāma tamasātīraṁ jāhnavyās tv avidūrataḥ (Rām 1.2.3)

He went to the bank of the river Tamasā, not far from the Gaṅgā accompanied by his disciple Bhardvāja. Interestingly, Dr. Rao interpreted Tamasā to mean peaceful or placid rather than the more common understanding of dark or ignorant. Observing the clear foreshore, the clear stream, he addresses his disciple:

śiṣyam āha sthitaṃ pārśve dṛṣṭvā tīrtham akardamam (Rām 1.2.3c)

akardamam idaṃ tīrthaṃ bharadvāja niśāmaya

ramaṇīyaṃ prasannāmbu sanmanuṣyamano yathā (Rām 1.2.4)

“Look at the pure, clear water of this river – not turbid at all (akardama).” He likens the waters to the mind of a good man (sanmanuṣya manaḥ) – clear and still, an image that evoked the yogic idea of citta-prasādana (PYS 1.33). Vālmīki’s imagination is still at work – the possibility of perfect good exists in man, and the still pellucid waters of the Tamasā remind him of that. He wants to take a dip, to experience the excellent purity.

idam evāvagāhiṣye tamasātīrtham uttamam(Rām 1.2.6c,d)

sa śiṣyahastād ādāya valkalaṃ niyatendriyaḥ

vicacāra ha paśyaṃs tat sarvato vipulaṃ vanam (Rām 1.2.8)

He is going to immerse himself (avagāhiṣye) in the water. Dr. Rao said avagāhna is a very loaded word in Sanskrit – much deeper than just a physical immersion. He takes his garment from the student but does not immediately enter the water. As he ambles towards the water, he looks at the expanse of the forest (vipula vana) all around, enjoying the sylvan surroundings as he enjoyed the sight of the river. There is unity between his internal state of mind and the world around him – his sense of peace and possibility is enhanced. There he sees a pair of krauñca birds in a state of physical union (mithuna), moving undisturbed (carantam anapāyinam) and making lovely sounds (cāruniḥsvanam).

tasyābhyāśe tu mithunaṃ carantam anapāyinam

dadarśa bhagavāṃs tatra krauñcayoś cāruniḥsvanam (Rām 1.2.9)

Suddenly, within a fraction of a second, the whole scene changes. As he (Vālmīki) was watching the mating birds, a hunter, abode of hatred and intent on evil, kills the male bird (eka pumāṃsa):

tasmāt tu mithunād ekaṃ pumāṃsaṃ pāpaniścayaḥ

jaghāna vairanilayo niṣādas tasya paśyataḥ (Rām 1.2.10)

Seeing the blood-stained body of her husband on the ground, struggling for life, the wife cried piteously:

taṃ śoṇitaparītāṅgaṃ ceṣṭamānaṃ mahītale

bhāryā tu nihataṃ dṛṣṭvā rurāva karuṇāṃ giram (Rām 1.2.11)

Seeing the bird slain in this manner by the niṣāda, compassion (kāruṇyam) arose in the kind souled ṛṣi:

tathā vidhiṃ dvijaṃ dṛṣṭvā niṣādena nipātitam

ṛṣeḥ dharmātmānaḥ tasya kāruṇyaṃ samapadyata (Rām 1.2.13)

tataḥ karuṇaveditvād adharmo ‘yam iti dvijaḥ

niśāmya rudatīṃ krauñcīm idaṃ vacanam abravīt (Rām 1.2.14)

Seeing the wailing female (krauñcī) and feeling compassion, Vālmīki, the dvija said – this is ‘adharma’. Dr. Rao commented on the use of ‘dvija‘ (twice born) for the bird and the brahmin ṛṣi – suggesting the one-ness between them. Vālmīki exclaimed:

“You [wretched] hunter, may you never find a permanent place for all of time [or may you never find fame], having killed a mating male krauñca in the throes of passion.”

mā niṣāda pratiṣṭhāṃ tvam agamaḥ śāśvatīṃ samāḥ

yat krauñcamithunād ekam avadhīḥ kāmamohitam (Rām 1.2.15)

Pratiṣṭhā is a special word. It denotes a kind of status. Even when a deity is installed or ‘established’ in a temple, the process is called pratiṣṭhā. A less common interpretation of the word is death, leading some commentators to believe that Vālmīki threatened the hunter with death. However, Dr. Rao was more inclined to connect Vālmīki’s words with the myth of the hunter who is always on the move, without a permanent abode. And this is their fate because of the hunter who shot down a bird while it was mating – an act that symbolises regeneration and sustainability. Hunters must kill – that is their profession, but not birds who are in the act of love.

Dr. Rao then suggested a code of conduct – even hunters have to hunt in a sustainable manner. And if one breaks the code, there is a price to pay. He shared a childhood tale from the life of Oodgeroo Noonuccal, an Australian aboriginal author also known as Kath Walker. The story was read most beautifully by Dr. Aparna Rao. It told of a poor family on very meagre rations. The children supplemented their food by hunting. But they had been instructed by the father to hunt only what they needed for food. Not to kill needlessly. One day annoyed by his siblings laughing at him, her oldest brother lashed out in anger, fatally injuring a kookaburra bird. On seeing the plight of the bird, the father of the children put it out of its misery. The children had broken the sacred law – never to kill for the sake of killing. And they had destroyed a bird that they were forbidden from destroying. Aborigines don’t eat the kookaburra, its merry laughter going unchecked. The punishment was that the children were not allowed to hunt or use their weapons for three months. For those three months their stomachs were constantly growling and they only got to eat ‘the white mans hated rations.’ The consequence of breaking the code.

We returned to Vālmīki, who found himself cursing the hunter – something he is not accustomed to, being a man of peace. Losing his temper made him uncomfortable. Afflicted with sorrow for the bird, what is that that has come forth from me, he wonders…:

tasya evam bruvataḥ cintā babhūva hṛdi vīkṣataḥ

śokārtena asya śakuneḥ kim idam vyāhṛtam mayā (Rām 1.2.16)

The sage, who was very intelligent, examining the matter, made up his mind and addressed his student:

cintayan sa mahāprājñaś cakāra matimān matim

śiṣyaṃ caivābravīd vākyam idaṃ sa munipuṃgavaḥ (Rām 1.2.17)“What came forth from me, overcome by sorrow is a śloka – a new verse form, and none other. Because it has four quarters, each one having an equal number of syllables – and this structure enables it to be accompanied by the cadence of stringed instrument, tantrī being the vīṇā.”

pādabaddho ‘kṣarasamas tantrīlayasamanvitaḥ

śokārtasya pravṛtto me śloko bhavatu nānyathā (Rām 1.2.18)

Vālmīki, having bathed, returns to his āśrama and goes about his duties mechanically, while being mentally preoccupied by his new creation. Then he as another visitor – the creator Lord Brahmā himself, of great resplendence and four faces, who has dropped in to see the bull among munis – Vālmīki.

ājagāma tato brahmā lokakartā svayaṃprabhuḥ

caturmukho mahātejā draṣṭuṃ taṃ munipuṃgavam (Rām 1.2.23)

Vālmīki having seen him rises and greets him with folded hands but is highly bemused:

vālmīkir atha taṃ dṛṣṭvā sahasotthāya vāg yataḥ

prāñjaliḥ prayato bhūtvā tasthau paramavismitaḥ (Rām 1.2.24)

He follows the hospitality protocol, offering his distinguished guest a seat. But his mind was still preoccupied with the events that had just occurred. The hunter must have been truly evil to commit such a heinous act, killing birds, who were making such beautiful sounds, for no reason at all. And thinking about that krauñcī he sang the verse again:

tad gatenaiva manasā vālmīkir dhyānam āsthitaḥ

pāpātmanā kṛtaṃ kaṣṭaṃ vairagrahaṇabuddhinā (Rām 1.2.28)yas tādṛśaṃ cāruravaṃ krauñcaṃ hanyād akāraṇāt

śocann eva muhuḥ krauñcīm upaślokam imaṃ jagau (Rām 1.2.29)

The creator smiling gently at Vālmīki said – “what you have created is [indeed] a new form of poetry [and] no other examination is called for. O Brahmin, this speech (sarasvatī) of yours has come forth by my will (macchandāt) alone”:

śloka eva tvayā baddho nātra kāryā vicāraṇā

macchandād eva te brahman pravṛtteyaṃ sarasvatī (Rām 1.2.29)

But what will he do with this new form of poetry? The Creator tells him to tell the complete (kṛtsnam) story of Rāma, as told to him by Nārada. He is to tell all that is knows and even that which is secret. Not just the story of Rāma, Lakṣmaṇa and the demons but also the story of Sītā.

rāmasya caritaṃ kṛtsnaṃ kuru tvam ṛṣisattama

dharmātmano guṇavato loke rāmasya dhīmataḥ (Rām 1.2.32)vṛttaṃ kathaya dhīrasya yathā te nāradāc chrutam

rahasyaṃ ca prakāśaṃ ca yad vṛttaṃ tasya dhīmataḥ (Rām 1.2.33)rāmasya saha saumitre rākṣasānāṃ ca sarvaśaḥ

vaidehyāś caiva yad vṛttaṃ prakāśaṃ yadi vā rahaḥ (Rām 1.2.34)

Brahmā reassures him further. Even those facts which he does not know will become known to him. This is the germ of the creative process. As the story unfolds, everything will be revealed to him. And not one word he utters in this great poem (kāvya) will be untrue (anṛtā). For the poet (kavi) sees even what the sun (ravi) cannot see:

tac cāpy aviditaṃ sarvaṃ viditaṃ te bhaviṣyati

na te vāg anṛtā kāvye kā cid atra bhaviṣyati (Rām 1.2.35)

Further reassurance is forthcoming. The new poetic form that has come forth from Vālmīki must be put to good use. He must create the virtuous and pleasing story (kathā) of Rāma bound by the śloka. And as long as the mountains and rivers exist on earth, the story of Rāma will spread widely on the earth. Here Dr. Rao quipped that Brahmā clearly had not heard of climate change which threatens to destroy all that we take for granted!:

kuru rāma kathāṃ puṇyāṃ ślokabaddhāṃ manoramām

yāvat sthāsyanti girayaḥ saritaś ca mahītale (Rām 1.2.36)

tāvad rāmāyaṇakathā lokeṣu pracariṣyati

And not just that – there is an assurance of wide readership and renown:

yāvad rāmasya ca kathā tvatkṛtā pracariṣyati (Rām 1.2.37c)

tāvad ūrdhvam adhaś ca tvaṃ mallokeṣu nivatsyas

ity uktvā bhagavān brahmā tatraivāntaradhīyatai (Rām 1.2.38)

And till such time as the story of Rāma spreads on earth, you will dwell [flourish?] in the worlds above, below and in my own abode too. Having said that, Brahmā disappeared. And here we are, some three thousand years later, in a foreign country discussing the Rāmāyaṇa and Vālmīki. Meanwhile at the āśrama there was much rejoicing. The students sang the śloka repeatedly with great joy. The verse form with balanced syllables and four parts which emerged from his grief (śoka):

samākṣaraiś caturbhir yaḥ pādair gīto maharṣiṇā

so ‘nuvyāharaṇād bhūyaḥ śokaḥ ślokatvam āgataḥ (Rām 1.2.40)

And he decided to write the entire story of Rāma, this great poem (kāvya):

tasya buddhir iyaṃ jātā vālmīker bhāvitātmanaḥ

kṛtsnaṃ rāmāyaṇaṃ kāvyam īdṛśaiḥ karavāṇy aham (Rām 1.2.41)

The celebrated sage authored the story of Rāma with lofty words and meaning, pleasing to the mind, with balanced syllables – in hundreds of verses (in fact twenty four thousand):

udāravṛttārthapadair manoramais; tadāsya rāmasya cakāra kīrtimān

samākṣaraiḥ ślokaśatair yaśasvino; yaśaskaraṃ kāvyam udāradhīr muniḥ

(Rām 1.2.42)

The epic thus composed had simple compounds, conjoined words, did not overlook any rules of grammar, was elegantly put together. It is the story of the best of Raghu’s descendants, about the destruction of the one with ten heads (Rāvaṇa). Composed by a muni, you all must listen:

tad upagata samāsa sandhi yogam

sama madhuropanata artha vākya baddham

raghuvara caritam munipraṇītam

daśa śirasaḥ ca vadham niśāmayadhvam ( Rām 1.2.43)

However great a story is, unless it is ‘published’ and reaches an audience, it could well fade away, without any recognition. At the start of the session, Dr. Rao had said in the age of orality, performance was the equivalent of publication in our times. He then told us about the first command performance of the Rāmāyaṇa which was commissioned ironically by Rāma himself.

As Vālmīki pondered about who could perform this magnum kāvya two handsome youths proficient in the Vedas and dressed like hermits touched his feet. They are Lava and Kuśa, who memorise the epic under Vālmīkiā’s tutelage. It is an epic which is full of musical complexity and beauty and has all the rasas one would expect from a great Sanskrit work.

pāṭhye geye ca madhuraṃ pramāṇais tribhir anvitam

jātibhiḥ saptabhir baddhaṃ tantrīlayasamanvitam (Rām 1.4.8)hāsyaśṛṅgārakāruṇyaraudravīrabhayānakaiḥ

bībhatsādirasair yuktaṃ kāvyam etad agāyatām (Rām 1.4.9)

Lava and Kuśa, accomplished musicians evidently begin performing the epic and it gathers renown. Rāma is now king of Ayodhyā. He invites them to his palace for a performance:

imau munī pārthivalakṣmaṇānvitau; kuśīlavau caiva mahātapasvinau

mamāpi tad bhūtikaraṃ pracakṣate; mahānubhāvaṃ caritaṃ nibodhata

(Rām 1.4.35)

Rama says – these two munis endowed with the marks of royalty are great tapasvins. The story is uplifting even for me to listen to. On Rāma’s say so, they begin performing in the ‘mārga’ convention. And Rāma gets totally engrossed in the story:

tatas tu tau rāmavacaḥ pracoditāv; agāyatāṃ mārgavidhānasaṃpadāsa cāpi rāmaḥ pariṣadgataḥ śanair; bubhūṣayāsaktamanā babhūva (Rām 1.4.36)

Reminding us that if even the hero of the story can feel a sense of upliftment, listening to the story or Rāma – what the of mere mortals like us?!

Dr. Rao ended the session as he had begun it – with another set of auspicious verses.

________________________________________________________________

1 Rao, A., “Two Performance Styles Based on Hindu Textual Heritage”

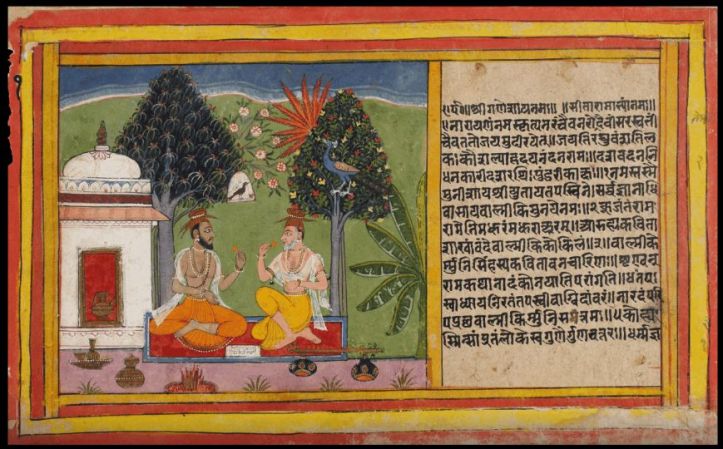

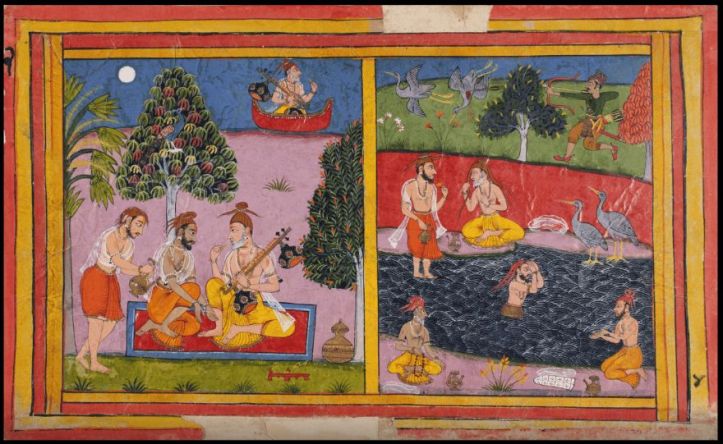

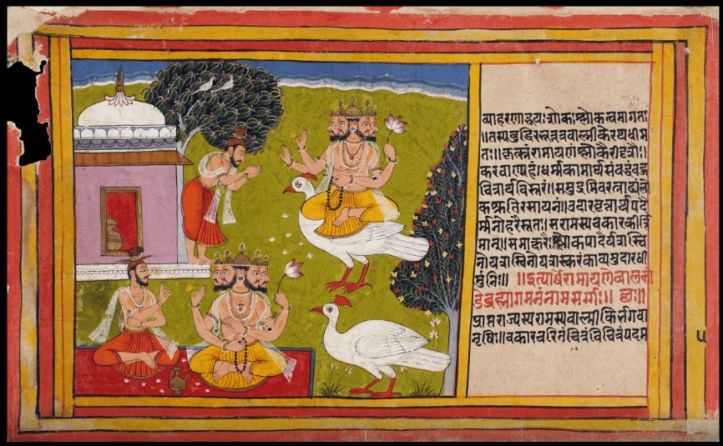

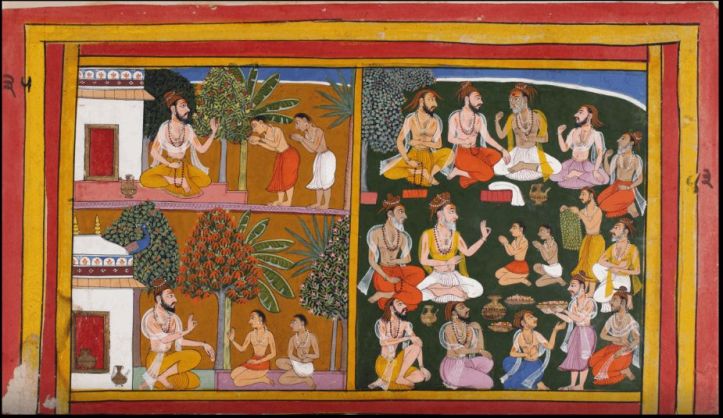

Mewar Ramayana: All images from the Mewar Ramayana can have been given open access and can be found at the British Library online gallery http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/whatson/exhibitions/ramayana/index.html © Trustees, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (formerly Prince of Wales Museum of Western India), Mumbai, India

Further reading: “Many Ramayanas. The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia,” Edited by Paula Richman, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS, Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1991 The Regents of the University of California – open access here